The Brookbush Institute Publishes a NEW Article: 'Levels of Evidence are Flawed'

The Brookbush Institute continues to enhance education with new articles, new courses, a modern glossary, an AI Tutor, and a client program generator.

Most levels-of-evidence hierarchies claim that higher levels represent “higher quality” evidence. However, “quality” is rarely defined in terms of measurable quantities such as error rates. ”

NEW YORK, NY, UNITED STATES, December 17, 2025 /EINPresswire.com/ -- Excerpt from the NEW Article: Levels of Evidence are Flawed— Dr. Brent Brookbush, CEO of Brookbush Institute

- Related Article: Is There a Single Best Approach to Physical Rehabilitation?

- New Glossary Term: Regional Interdependence

Introduction: When a Heuristic Becomes Dogma

Ask ten licensed professionals to explain how the different “levels of evidence” are ranked, and you are likely to get ten different answers. One might say “risk of bias.” Another might say “internal validity.” A third might say “strength” or “rigor” without being able to specify how that rigor is quantified. The most common answer may be “quality,” which is a particularly subjective term. If you press a little harder and ask, “What statistic, metric, or objectively measurable quantity were you referring to—error rate, reproducibility, effect-size accuracy?” the conversation usually stalls. The pyramid is treated as self-explanatory, even when few individuals, if anyone, can clearly state what is being measured along its vertical axis.

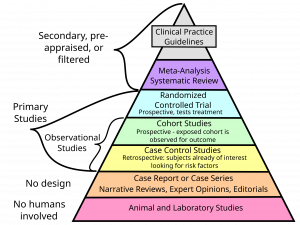

Despite this ambiguity, most evidence-based practice courses introduce the same visual: a pyramid with expert opinion and case reports at the bottom, observational studies in the middle, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) above them, and systematic reviews or meta-analyses at the very top. Library guides and teaching materials describe this as a hierarchy of “strength” or “quality” of evidence, and some explicitly define it as a ranking of studies according to the probability of bias. For example, the Simmons University Nursing levels-of-evidence guide states, “Levels are ranked on risk of bias – level one being the least bias, level eight being the most biased” (1). The Concordia University Wisconsin Social Work evidence-based practice guide similarly notes, “Higher levels of evidence have less risk of bias” (2). The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM), for example, presents levels of evidence that place systematic reviews of randomized trials at level 1 and expert opinion at level 5, and many derivative pyramids adopt the same basic ordering (3).

Originally, these hierarchies were introduced as pragmatic tools. Groups such as OCEBM developed levels-of-evidence tables to help guideline panels and journal editors prioritize studies when time and resources were limited (3). To our knowledge, they were never validated as instruments for measuring error rates across designs and were not intended to serve as universal truth meters. The problem is the shift from heuristic to dogma. Introductory courses on research often imply that study design categories are a direct proxy for “how true” a result is, so anything below a chosen level is dismissed as “low quality,” regardless of how the study was conducted or how much data it provides. In practice, this leads to rigid schemes in which large bodies of observational research are routinely down-ranked and ignored, while systematic reviews and meta-analyses are treated as the pinnacle of evidence, even though they do not generate new primary data and can amplify the biases of their inputs. The most problematic use of this logic is the dismissal of any study that is not a meta-analysis, combined with treating a meta-analysis that fails to refute the null as proof that the intervention does not work. (We discuss this fallacy further in “Meta-analysis Problems: Why do so many imply that nothing works? ”) In fields such as rehabilitation and disability, where blinding is often impossible, interventions are complex, and long-term practice-based outcomes may be more informative than short-term experimental trials, this structure tends to devalue some of the evidence that is most clinically relevant.

Quick Summary....

FOR THE COMPLETE PUBLICATION, CLICK THE LINKS ABOVE!

Brent Brookbush

Brookbush Institute

+ +1 2012069665 ext.

email us here

Visit us on social media:

LinkedIn

Instagram

Facebook

YouTube

TikTok

X

Other

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.